Buckminster Fuller, born in 1895, was one of the last New England Transcendentalists. Their influence can be seen in Fuller's rejection of established religious and political notions of the past and his ideas of a system of thought based on the unity of the natural world. While the Trascendentalists used experiment and intuition to better understand the natural world, Fuller also saw technology as being the means of understanding the universe; he was devoted to "applying the principles of science to solving the problems of humanity" (Fuller, 1965) .

He was ahead of his time in terms of understanding the limitations of natural resources and our impact on the environment. Fuller dedicated his life to finding an answer to the following question: "Does humanity have a chance to survive lastingly and successfully on planet Earth, and if so, how?". Fifty years before the popularization of the green movement and a biocentric view of nature, Fuller already developed a systemic worldview and was concerned with energy and material efficiency in his architecture and engineering projects. Unlike many of the "doom and gloom" environmental critics of today, Fuller remained optimistic about humanity and our future; in the 1970s he went so far to proclaim that competition for necessities was no longer important and that cooperation was key for survival-- he went so far as to say that war was obsolete.

While Fuller made many contributions to the realms of science and art throughout his long career, I want to focus on what he's most known for, the form of the geodesic dome. The word "geodesic" comes from Latin and means earth dividing-- thus a geodesic line is the shortest distance between any two points on a sphere. Fuller devised the geodesic dome as a way of optimizing structural advantage by using the least material possible. The dome uses a pattern of self-bracing triangles that allow for local loads to be distributed throughout the structure. In contrast to conventional buildings, geodesic domes get stronger, lighter and cheaper per unit of volume as their size increases.

Surprisingly, Fuller was not the first to come up with the geodesic dome, but he did develop it further and helped to popularize the concept more widely. Originally Walther Bauersfeld came up with the idea during WWI for the construction of a planetarium in Germany. It was Fuller, however, who applied the concept to domestic and industrial buildings. Originally Fuller thought the geodesic dome would be ideal for addressing the postwar housing shortages. Due to design drawbacks, the dome was instead mainly adapted for industrial and institutional use.

Buckminster's Fuller's most radical idea involving the use of a geodesic dome to enclose the entire city of Manhattan. It was conceived as a way of regulating weather and reducing air pollution.

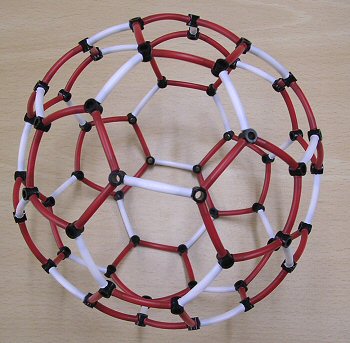

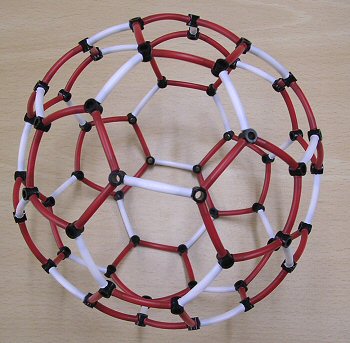

Unbeknownst to me, my first exposure to Buckminster Fuller was through my 11th grade AP chemistry class-- to better understand the structure of the spherical fullerene or "buckyballs." Little did I know at the time that the straw and marshmellow buckyballs we were creating had any connection to geodesic domes or the complex ideas of designer/architect/writer/inventor/visionary Fuller. Unfortunately the article by Elizabeth A.T. Smith already assumed we had an intimate knowledge of Fuller and his ideas and she only briefly references a concept when discussing how he influenced contemporary artists. Thus I did some of my own independent research to better understand Fuller and his ideas.

Where else has Buckminster Fuller's ideas infiltrated American Pop culture? Another example is a piece of playground equipment modelled on Fuller's geodesic dome. Children can climb up the latticework of the dome or swing from the bars at the top. Unfortunately most of these playground domes have been dismantled in recent years due to safety issues (they're made out of metal that can develop sharp edges/rust).

The Montreal Biosphère, designed by Fuller and built as the American Pavilion for the 1967 World Exhibition Expo. It was originally built from steel and clear acrylic and had seven levels of themed platforms. The clear bubble exterior burned in the 1970s; today the steel stucture surrounds the enclosed buildings of the Environment Museum.

The geodesic dome in an urban setting: Vancouver's Science World, originally built in 1986 for the Exposition on Transportation and Communication and designed by architect Bruno Freschi. Now it houses a hands-on science and technology museum geared toward children.

The first industrial building to be built in the design of a geodesic dome was the Union Tank Car building in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. It was designed by Fuller himself in 1958 as a repair station for railroad tank cars. Unfortunately it fell into disuse and disrepair and was eventually demolished by the Kansas City Southern Railroad in 2008 after a long battle by preservationists calling for its historical status.

Home Sweet Dome? Since the 1950s, companies like Geodesic Domes and Homes, Energy Structures and Good Karma Domes have been producing prefabricated homes influenced by Fuller's geodesic dome structure. The homes are touted as being more resistant to hurricanes and storms as well as being more energy efficient than traditional buildings. Fuller actually lived in a geodesic dome home in Carbondale, Illinois that still stands today. Contemporary dome houses are geared more towards an off-the-grid living lifestyle that does not necessarily jive with Fuller's ideas of the geodesic home as a cheap, easy-to-make option for the masses. His utopian idea did not catch on in the domestic market due to practical issues like roof leaks.

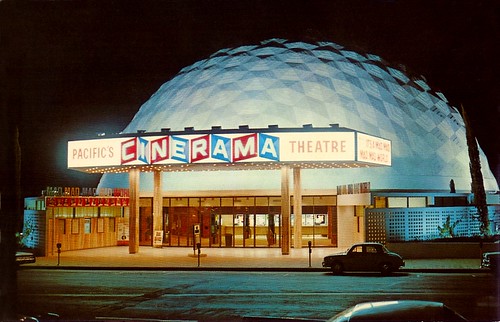

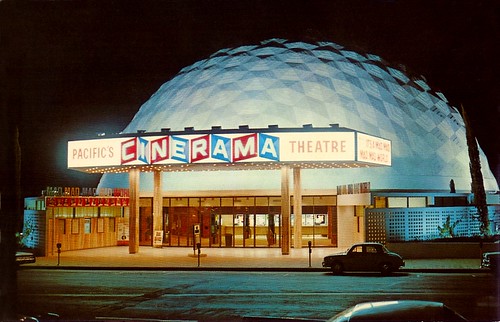

Located on Sunset Blvd in Hollywood is my favorite incarnation of Fuller's geodesic dome. Built in 1963, the Cinerama Dome took only 16 weeks to build and cost half the cost of a conventional building. The top image is a vintage postcard that shows the Cinerama Dome the year it opened. In 2002 it became integrated into a larger multiplex and renamed the Arclight; it hosts star-studded premieres for movies like Shrek and Spider Man (the bottom two images show how the dome is redecorated accordingly).